CONCEPT TO SEE:

EVENTS AND STORIES: TIME FRAMES FOR MEANINGS

Many factors influence our vulnerability to failing to see and understand what occurs in our interactions, all clustering around the complexity of information presented to us for analysis and decision. One example is how this information is presented to us. What we see is not a long, continuous scene; what we read or hear is not a long, continuous story. Instead, we are exposed to scenes and story segments that are discontinuous, sometimes out-of-order fragments requiring that we begin to piece them together, motivating us to solve the puzzle.

Moreover, we are not experiencing the scenes and stories of a single narrative; as we live our lives we are putting together the pieces of puzzles associated with many narratives, multiple scenes and stories. A seemingly endless number of voices are speaking to us in these scenes and stories, providing the information from which we learn to find our way through their mazes, or not.

Discussing meaning in the abstract creates the illusion that we are considering it as a neatly packed puzzle to be solved in isolation. Of course, this is not true. Our mind is besieged by continuous information from which we are extracting meanings and knitting these meanings into larger conceptual groups with expanded meanings. The meaning of a subject noun is linked to the meaning of the verb, along with other elements, creating the meaning of the sentence, which combines with meanings of other sentences to produce the meaning of the paragraph. Meanings occur at many levels, but two levels of meaning are of particular practical utility, an event and a story (or narrative), because each is a meaning group — in other words, each contains many meanings that draw our attention, meanings that are linked and grouped by common features of the event or story. Learning how meaning is understood in the event, and in the story, is essential to adapting in life.

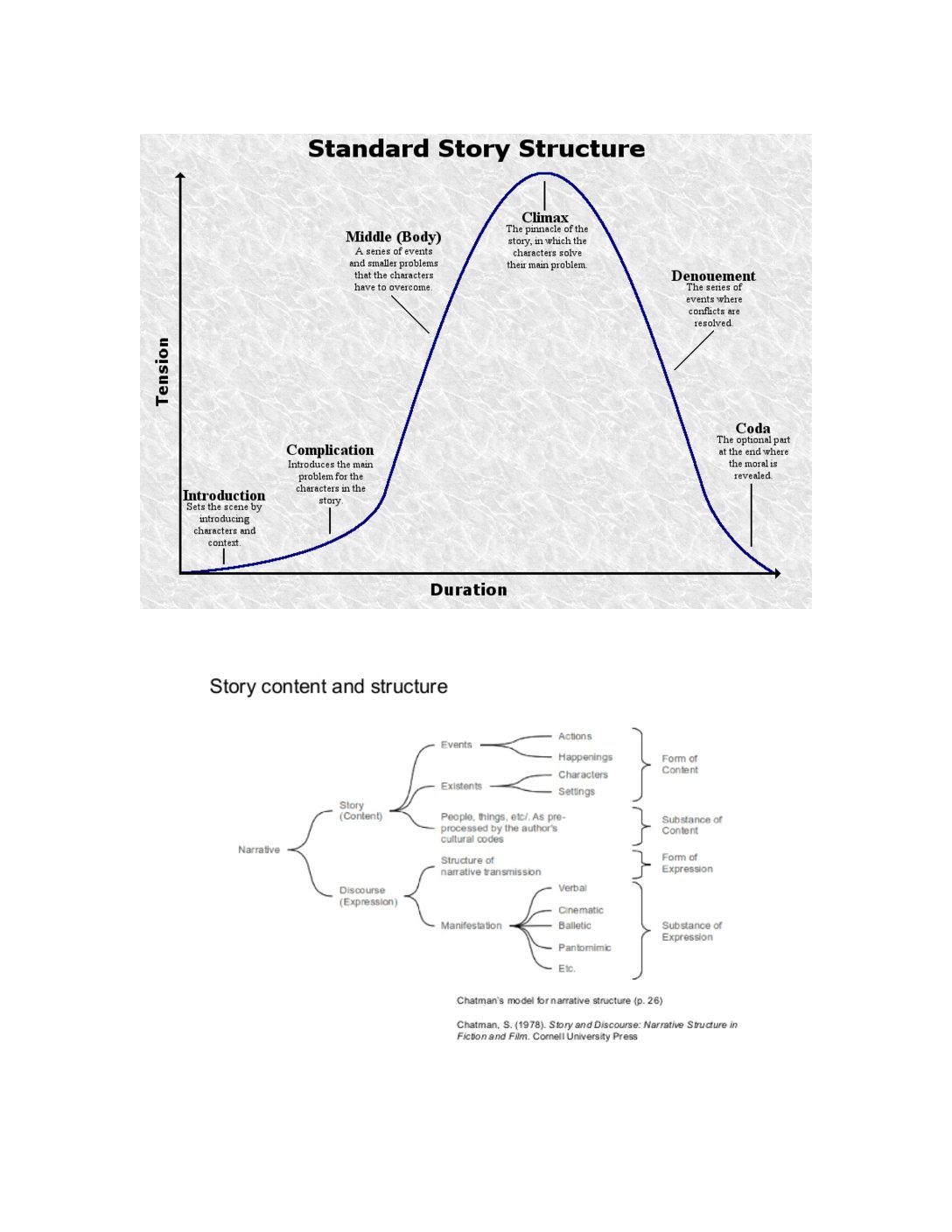

Life experience can be considered to be made up of brief events (of arbitrarily short length), many of which are linked into stories, various narratives, each of which might be thought of as a series of many events. A story in actual life is comparable to a short story or a novel in literature, or a television episode or series, or a video game or film, all depending upon their length. The structure of stories has been analyzed in depth in other disciplines, such as literature or film studies, producing theories of their elements and how they are organized. Our perspective at this time, however, will use only the simple dichotomy between event and story.

During childhood we learn how to follow a narrative, and the more we study this process the better able we are to understand details of the narrative and to differentiate branches of greater or lesser significance, and their causal relations. We improve our skills at “knowing what’s coming”, at predicting the ending (the outcome of a story).

In order to enhance our skills for following and understanding meanings in narratives of varying lengths, sources, and types, it is necessary to develop greater awareness of the occurrence, components, and impact of these narratives. This generates an improved skill for estimating meanings when one is exposed only to fragments of a narrative, which is the most common life experience — gaps in the stories of life are plentiful.

Opportunities are available in life for learning and practicing these skills, but commonly are not recognized, and initially are experienced as “too much work” — just as a five or six year old resists when a parent takes her to her first gymnastics or soccer or tennis or sailing class; yet, the work put in by the child can blossom into an activity loved and enjoyed for a lifetime.

Events in our lives, and in stories, are continuously occurring, requiring unceasing adaptive responses. The events can merit descriptors in retrospect, such as surprising, boring, thoughtless, kind, ambiguous, degrading, or an event involving a display of unusual valor. Events, and our responses to them, gradually define us in our own minds, and in the minds of others. They “tell my story”. The “reality” of each person — his inner world of thoughts, emotions, motivations, and intentions, and how they sculpt his behavior — is elusive to others, but others attempt to assemble a portrait of the person through “events”, interactions with the person, gossip about the person, and similar sources of information.

At the end of each event there is, inevitably, much incomplete information, leaving a sense of uncertainty and anticipation. “Long” events have multiple topics and several conflicts in which a large number of meanings are touched upon and play a central role in the emerging drama of the event — developed or not, expanding or disappearing, reappearing or not, and clarified or, more often, left murky with uncertainty as the event ends. Meanings shift, ebb and flow, often remaining incomplete shadows that can be used for the expression of anger or for manipulative purposes as emotions dominate. In the end, however, the event remains an event within a longer story; it is not the story.

A TASTE OF LIFE

Stories link events and give them meaning and significance. Therefore, we continually create stories to approximate the possible and probable meanings of events in which we participate. Stories require a tolerance for ambiguity, and a recognition of varied common elements of our lives, such as tedium, compassion, thoughtlessness, empathy, deception, and integrity, as they mirror life events. Participation in stories such as are found in novels or the internet, is “safe”, however — they are not real — and provides useful opportunities to enhance our capacity for following, organizing, and understanding a narrative — and the meanings within the narrative.

A story does not supply all information, but by the end there is less uncertainty and less incomplete information when compared to an event. A story provides a cohesive tracking of the thoughts, emotions, motivations, and actions of characters that make up the train of events, and the conflicts within and between them. A point of view for the story reaches its conclusion at the end. These characteristics of a story can even be seen in a summary of a story, although the brevity of the story summary favors that certain elements be left out — which can fit the artistic purpose — such as leaving out segments of the story involving conflict, tedium, the demands of work, and the like.

A TASTE OF LIFE

The story, or the narrative, is so essentially significant to the development of our capacities to understand increasingly complex meanings in our relationships with others, that narratives will be the focus and form of information presented in posts each Tuesday, beginning with Post 9.

To reach the goal of understanding whether and how hypothesized cultural hazards (e.g., meanings and altered meanings) are linked to destructive cultural outcomes, several approaches are possible for examining and identifying potential links with the outcomes. Examples include recalling existing precedents, clarifying the time frame problem (short-term or long-term), and designating a source of examples available for demonstration. Films provide the most vivid examples, but other story forms are very useful in other ways.

Stories have obvious advantages for demonstrating such links, if present, and the first (Post 9) of many stories to be presented provides a significant precedent, presents clear time-frame elements, and indicates how these examples can function; it is not a film, and, instead, utilizes text and music.