CONCEPT TO SEE:

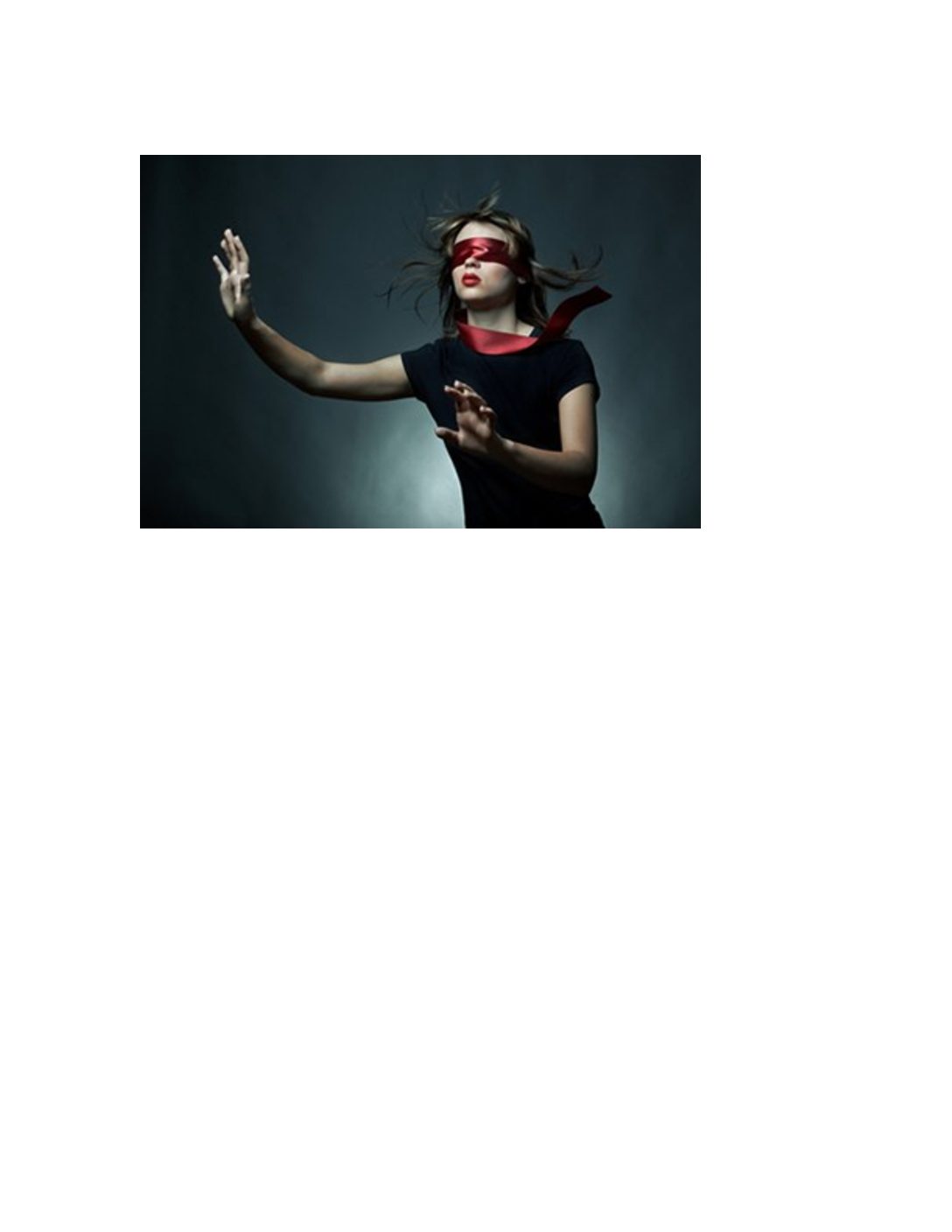

ACCEPTABLE BLINDNESS: CONVENIENT NEGLECT, CUMULATIVE RISK

Tampering with the odometer is, of course, only one example of acceptable sins. Are such sins actually “acceptable”? The fact that they seem endemic in our lives might suggest that they are – a little tampering is “no big thing”.

We might also consider the possible existence and contributions of another set of behaviors that permit the enjoyment of what will be called “acceptable blindness”.

Acceptable blindness is a lack of attention to, and an unawareness of, behaviors with a pronounced potential for not only harm to victims, but hidden cumulative destructive effects to social groups and societies.

The gratification that it provides stems from the avoidance of confrontation with an aggressor; entanglement in a confusing, risky dispute and potential controversy; and the use of significant effort in a matter not immediately involving oneself or offering obvious immediate incentives for gain.

If, following an instance of acceptable blindness, the blind observer appears confused or embarrassed, or even experiences the urge to comment about his neglect of the obvious destructive risk to the victim of the behavior observed, but does nothing, this does not qualify as a response, due to a failure of effective action.

Human acceptable sins might be ignored in the short-term with no apparent problem. Over time and over groups and populations, however, these behaviors can spread. If they are mild distortions of meaning with no damage to anyone, then it is likely that they will not disrupt social groups.

If the acceptable sins involve significant distortions, or even destruction, of meaning in individual cases, and damage to victims, then the effects of multiple interactions of this kind might build long term cumulative effects that are hidden. These hidden effects might nurture uncertainty, aggression, deception, and increasing confusion and disorder in the society. Simultaneously they could be accompanied by the acceptable blindness of observers to what should be obvious: harm to an individual and the risk of long-term cumulative effects that are destructive to our societies.

We confidently assert our abilities to manage our societies, yet wars, terrorism, and corrupt business practices persist. We confidently assert our capacity to manage our private lives, even as personal suffering in relationships and in work environments is too common. These enduring problems indicate that human behavior baffles us at many levels. New understanding of specific behavioral patterns is an initial step toward reducing those behaviors that have a high risk of causing harm.

An individual behavior is the final common pathway for an extraordinary amalgam of influences (both external and internal), culminating in a decision and a behavior that is part of a linked sequence of behaviors. Acceptable blindness, therefore, is a result of numerous emotions, thoughts, and motivations, which, of course, are not “visible” to others. However, acceptable blindness can characterize the behavior of groups, as well, and in groups the competing influences of such emotions, thoughts, and motivations are commonly evident in the behaviors and communications leading to group decisions and actions. Group actions characterized by acceptable blindness are instructive about why and how acceptable blindness occurs, particularly the pivotal roles of emotions and motivations.

A TASTE OF LIFE

VOICES

‘The English never draw a line without blurring it.’

Winston Churchill

At last Ralph stopped. He was shivering.

‘Piggy.’

‘Uh?’

‘That was Simon.’

‘You said that before.’

‘Piggy.’

‘Uh?’

‘That was murder.’

‘You stop it!’ said Piggy, shrilly. ‘What good’re you doing talking like that?’

He jumped to his feet and stood over Ralph.

‘It was dark. There was that — that bloody dance. There was lightning and thunder and rain. We was scared!’

‘I wasn’t scared,’ said Ralph slowly, ‘I was — I don’t know what I was.’

‘We was scared!’ said Piggy excitedly. ‘Anything might have happened. It wasn’t – what you said.’

He was gesticulating, searching for a formula.

‘Oh Piggy!’

Ralph’s voice, low and stricken, stopped Piggy’s gestures. He bent down and waited. Ralph, cradling the conch, rocked himself to and fro.

‘Don’t you understand, Piggy? The things we did –‘

‘He may still be –‘

‘No.’

‘P’raps he was only pretending –‘

Piggy’s voice tailed off at the sight of Ralph’s face.

‘You were outside. Outside the circle. You never really came in. didn’t you see what we – what they did?’

There was loathing, and at the same time a kind of feverish excitement in his voice.

‘Didn’t you see, Piggy?’

‘Not that well. I only got one eye now. You ought to know that, Ralph.’

Ralph continued to rock to and fro.

‘It was an accident,’ said Piggy suddenly, ‘that’s what it was. An accident.’ His voice shrilled again. ‘Coming in the dark—he had no business crawling like that out of the dark. He was batty. He asked for it.’ He gesticulated wildly again.

‘It was an accident.’

‘You didn’t see what they did –‘

‘Look, Ralph. We got to forget this, We can’t do no good thinking about it, see?’

‘I’m frightened. Of us. I want to go home. O God I want to go home.’

‘It was an accident,’ said Piggy stubbornly, ‘and that’s that.’

William Golding (1954/2009). Lord of the Flies. London: The Folio Society, pp. 172 – 173.