THE MEANING MAZE

THE MUTILATION OF MEANING

Following the path of meaning in the lives of those in the emerging German resistance of the early and mid-1930s, a period of great uncertainty and confusion mixed with frightening danger, is a story of immediate peril in conflict with an enduring moral awareness — refusing to neglect the meaning of events around them.

VOICES

Each of the lawyers in the family — Klaus Bonhoeffer and the three brothers-in-law Rüdiger Schleicher, Hans von Dohnanyi, and Gert Leibholz, along with the almost-family Justus Delbrück — faced, in different ways, the Nazis’s assaults on the very essence of the law, not to mention the unremitting Nazi attacks on Jewish lawyers and lawyers deemed politically “unreliable.” Despite growing risks, they engaged in oppositional, then resistant acts; eventually this resistance work took over their lives. . . .

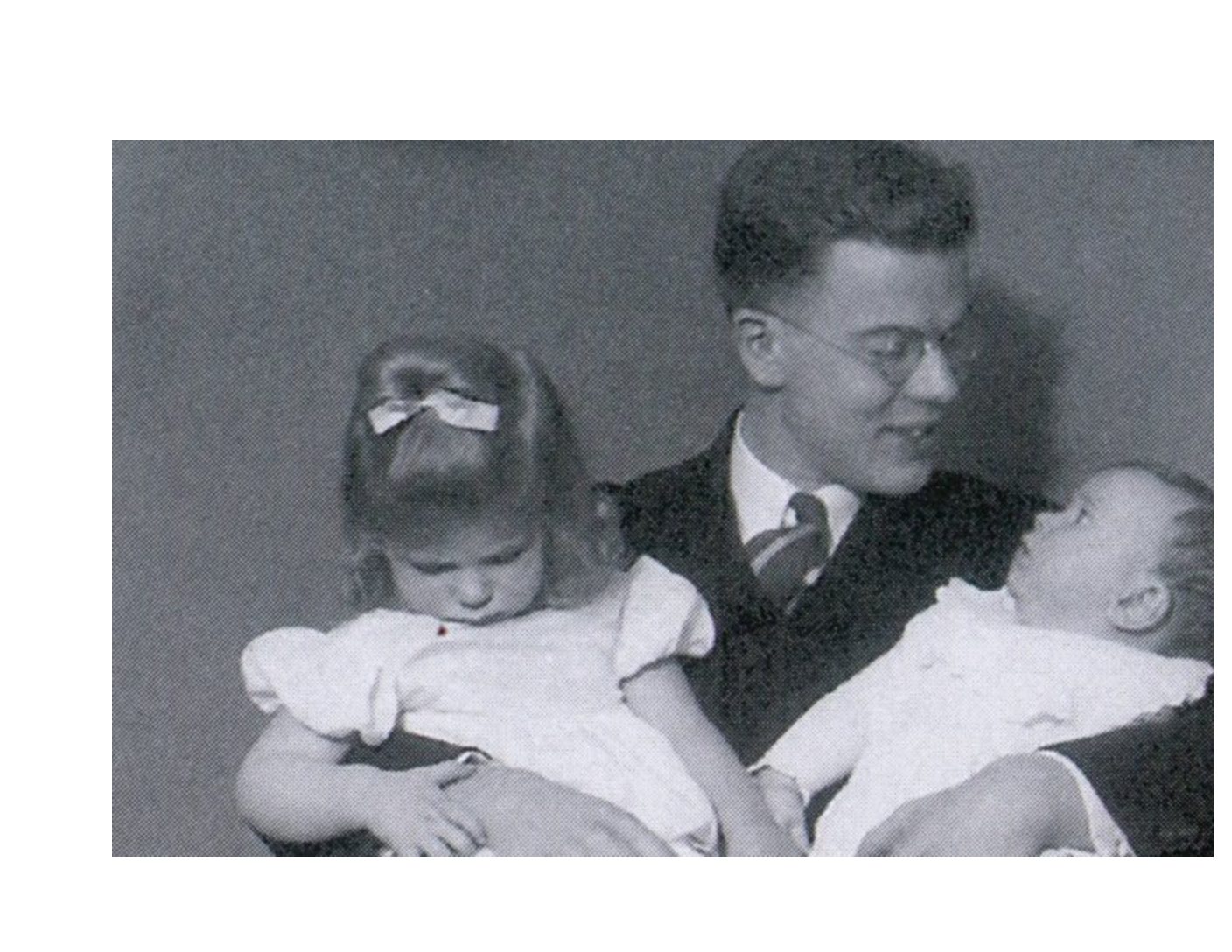

It was in Hamburg that Christine, a budding botanist, reluctantly gave up her science to assume the traditional wifely, motherly role in their growing family. In 1929 they returned to Berlin when Hans entered the Ministry of Justice working for State Secretary Curt Jöel (like Mendelssohn-Bartholdy a converted Jew). With his passionate interest in Weimar politics and his unconditional, patriotic support of the Republic, Hans was, like Rüdiger Schleicher, more fervent and outspoken in his democratic convictions than other family members. Converted Jews were among his closest friends and admired superiors — an additional reason for him to find Nazi anti-Semitism repellent.

In June 1933, Dohnanyi became the chief assistant to Franz Gürtner, a former Bavarian minister of justice. In 1932 Gürtner had willingly become Reich minister of justice under Chancellor Franz von Papen and then under Kurt von Schleicher — he favored their authoritarian plans; like them he had no use for the Weimar Republic or for democratizing reforms of any sort. But as Hitler’s state developed its totalitarian form, Gürtner, a genuine conservative, found himself fighting — and losing — battles to retain the last vestiges of a legal order. He had to participate (as did, occasionally, his aide Dohnanyi) in interministerial deliberations on a Nazified penal code, for example; nothing came of that particular effort, but Gürtner was coming to understand the criminality of the regime. Dohnanyi went with Gürtner to an appointment with Hitler that first summer at his new retreat at Obersalzberg. On his return, Christine recalled, he told her, “The man is mad.”

Gürtner stuck to his post, though, “to prevent worse from happening.” A genuine servant of the law, he had to facilitate its degradation into violence. And Hans knew that, as Marikje Smid wrote, he too “had become against his will a part of the National Socialist system.” At one point Gürtner said to Christine, “National Socialism is a feverish disease of the German people. And as long as the fever lasts, a doctor cannot leave the patient’s bed, even when he thinks there is nothing more he can do.” obviously there are many ways to read this sentence, but that it depicts a sharp inner conflict should be acknowledged.

Hitler had kept Gürtner on so as to reassure people that the “law” remained in non-Nazi hands. But the Gestapo and Heinrich Himmler’s SS (Schutzstaffel), aiming at virtually full autonomy and unlimited power, kept the Justice Ministry under surveillance.

Still, as Gürtner’s confidant, Dohnanyi usually knew ahead of time about new laws being planned by the Nazis, and he passed on useful, important information to his brother-in-law; Dietrich in turn kept him abreast of the ecclesiastical conflicts. And he also advised colleagues and friends who had become victims of Nazi rule. To Christine, he called this work, often conducted in his office, “my Privatpraxis,” a term borrowed from the medical profession.

Even more remarkably, with cool-headed efficiency and rising outrage Dohnanyi began to keep a chronological record, along with supporting evidence and an index, of the regime’s illegal acts. These documents were meant to facilitate the prosecution of Nazi criminals after the end of the regime. He began this in October 1934, after the Prussian and Reich ministries of justice were merged and Gürtner appointed him as the chief of his ministerial office. He kept track of the details of particular measures taken against clergy and Jews, and of the many instances when the party, the Gestapo, the SA, and the SS violated legal norms — from arbitrary detentions and torture to currency swindles and other financial crimes committed by local Nazi chieftains; eventually the file (in postwar years it came to be called the “Chronicle of Shame”) included documentation on the persecution of Jews, details and evidence about Nazi atrocities in Poland in 1939 and in the east after 1941. Gürtner knew about this record-keeping and apparently approved of it. (And he allowed Dohnanyi to keep the documents even when he left the Ministry of Justice.) The records were stored in an army safe, Dohnanyi having been assured of its inviolability, at the military base in Zossen, some twenty miles from Berlin.

Like all civil servants, Dohnanyi had to submit proof of unblemished Aryan descent — but he could not. The files yielded incriminating information that his maternal grandfather was Jewish. In 1936, in a routine meeting with Hitler, Gürtner told him there were some difficulties with his indispensable personal duty, but Hitler declared, “Dohnanyi should not suffer any disadvantage because of his racial origins [Abstammung]. Still, it wasn’t until March 1940 that Dohnanyi received official confirmation of his and his sister’s racial “purity.” The fervent Nazi Roland Freisler, a fellow lawyer in the Justice Ministry and already a political and personal enemy of Dohnanyi’s, indirectly called for a ministerial inquiry, which ended with a report sent to Hitler’s deputy labeling Dohnanyi as “half German, quarter Hungarian, and quarter Jew.”

Elizabeth Sifton and Fritz Stern (2013). No Ordinary Men: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Hans von Dohnányi, Resisters Against Hitler in Church and State. New York: New York Review Books, pp. 45 – 47

Accompanying music:

Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 3 in E Flat, 2. Marcia Funebre: Adagio Assai

Christoph von Dohnányi, The Cleveland Orchestra & Chorus, Telarc Digital

1 Comment